After most of an apartment building in the Miami area spontaneously collapsed in June, Catherine Harmon Courage, a writer for Scientific American, sat down with social scientist and clinician Pauline Boss to learn about the fuzzy loss zone The special sadness that comes. For example, this type of loss occurs when the body of a relative cannot be recovered from an accident or the child is missing. It is possible that this person has already left, but there is no certainty. In the stress and anxiety of the pandemic, this uncertainty sounds very real-it is not known whether you or your loved one will get sick, or whether your job is secured, or how to balance childcare and COVID restrictions. Boss told our reporter how humans can build tolerance for ambiguity. But I don’t think this makes it easier (see “The obscure loss caused by the collapse of an apartment in the Miami area makes grief more difficult”). As many psychological studies have shown, no matter what kind of sadness, sadness requires patience and compassion—especially for oneself.

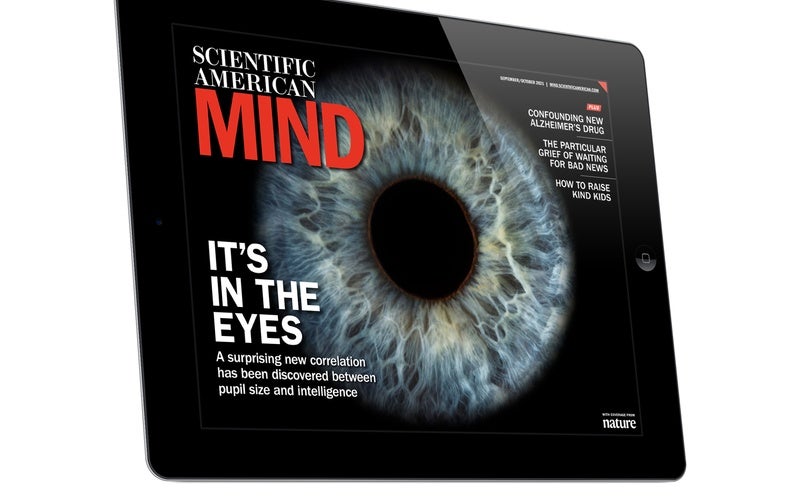

This question is full of other interesting findings. Current research shows that human intelligence can be collected through certain eyeball sizes (see “Pupil size is a sign of intelligence”). Senior editor Clara Moskowitz selected the brain of Melinda Wenner Moyer. His new book details the scientific methods of teaching children to be generous, honest, helpful, and kind ( See “How to raise children who will not grow up to be bastards (or worse)”). In today’s world, sometimes people feel that goodwill is in short supply. We better cultivate it in our own home.

This article was originally published on SA Mind 32, 5, 2 (September 2021) with the title “On Kindness and Grief”

doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0921-2