You have it, you should be able to fix it. Many equipment sold today are either designed to be unmaintainable, or too complicated to maintain, or can only be maintained with professional tools that are only available to authorized service agents, or there are no repair parts available. In an era when sustainable development has become a global concern, this is a hot issue. Therefore, after years of inaction, global legislators and regulators have finally put it in their sight and become a buzzword.But what is it Yes Repair right, what do we want it to be?

Is it designed for maintenance?

The first question to consider is: If something is specifically designed for lack of repairability, does it matter whether you have the right to repair it? Consider a typical household pod coffee machine, such as a Tassimo or similar device: although it is a very simple device physically, its disassembly and reassembly are particularly complicated. When something goes wrong, you cannot enter it.

Should it be the responsibility of the regulatory agency to require design to be easy to maintain? We think so. There are other forces affecting the designers of home appliances; manufacturing-oriented considerations and appearance issues directly affect the company’s bottom line, and the end-user repair experience is often ranked last, although the benefits at the national level are obvious. This is the purpose of the law.

Have other laws been abused to reduce maintenance?

In many cases, there is no such thing as a lack of maintenance rights. The coffee machine at Oxford Hackspace is broken and it may be difficult to repair, but I have every legal right to do so.

Turn to the typical representative of many maintenance rights stories: John Deere. Because the machine itself is designed for work, farmers should obviously be able to twist their tractors.

Here, Deere turned to the DMCA, which was a piece of legislation formulated in the 1990s by the music industry against the panic of piracy to prohibit the circumvention of copyright protection mechanisms. Similar to the method used to sterilize refilled printer cartridges, Deere bundles a software component that must be linked to and authorized by the Deere computer. Although farmers can repair their tractors, it will no longer work after unauthorized repairs. Only Deere or its agents can perform the repaired part of the software, bypassing it would violate the DMCA. Should regulators have the power to prohibit reductions in repairability by linking this process to other legislation? We think so.

Does unnecessary complexity hinder repairability?

It’s all good to have something designed for repairs and not hindered by legal barriers, but there are other ways for manufacturers to hinder the repairability of their products. When a simple product becomes unnecessarily complicated, it not only increases the possibility of failure, but also increases maintenance costs. This is in the interests of manufacturers who want to sell new products, not consumers. Deere tractor parts once again provide an example, one of which is a simple part with a chip; previously there was only a simple mechanical or hydraulic part, and now there is an unnecessary electronic device.

Anyone who has maintained a car made in the 1980s and a car made ten years ago will understand this; the former has only a light bulb and a switch for lighting, the latter now uses microcontrollers in the switches and lights to accomplish exactly the same tasks . Those who are prepared to defend this approach by describing the advantages of the CAN bus should reflect on the current shortage of chips and the reasons for the unnecessary proliferation of automotive microcontrollers. Should regulators raise questions about unnecessary product complexity to hinder repairability? We think so.

Is the widget hidden in the module?

Considering that a product is easy to repair and easy to use, we will turn to the issue of parts availability. This is a favorite trick of domestic appliance manufacturers to eliminate their old products by removing spare parts from the market, and this approach has also attracted attention along with the EU’s attitude to this issue.

For example, they require parts for washing machines to be sold within ten years of manufacture, but it is worth considering: What are parts? Common sense suggests that any component capable of failure should be available, but this is an explainable definition.

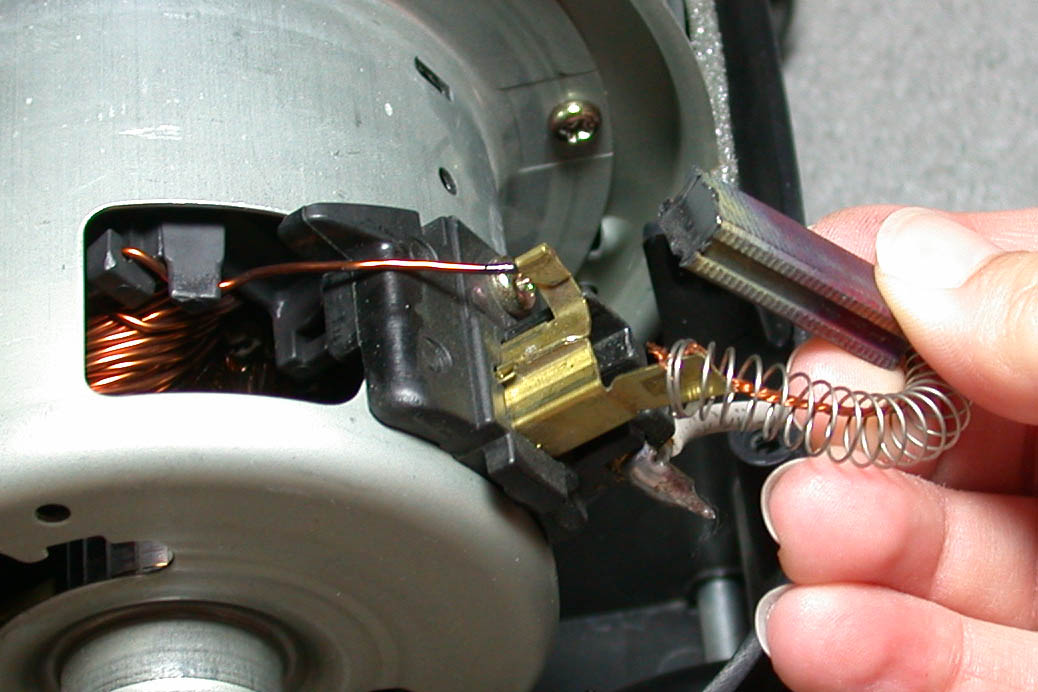

Imagine a motor with a faulty brush. You might want to go to a parts store to buy a set of replacement brushes. But an unethical manufacturer can designate the motor as a part instead of a brush, which means that a few-dollar part becomes a many-dollar part. Other examples of small fragile parts contained in more expensive parts assemblies include bearings or seals that cannot be replaced by themselves. Does the regulatory agency have the right to require replaceable wear parts to be provided separately, rather than only included in larger components? We think so.

Is there enough information to fix it?

Finally, it is understood that many devices today need to be computerized. For example, we may have complained about the unnecessary excessive use of microcontrollers in motor vehicles, but it is undeniable that many functions in modern cars can only be achieved through the use of microcontrollers. Because their diagnostic functions are an important part of repair, it is vital that they cannot restrict repairability by restricting access to information, software, protocols, and error codes. American farmers have to resort to Eastern European software piracy to access the systems on their Deere tractors. Although car owners around the world can plug in OBD-2 dongles, most of the information that can still be accessed still has ownership. Should regulators require documents, diagnostic protocols and software to be made available to everyone? We think so.

This article is close to the declaration in stating the key points that we believe should be considered when evaluating the right to repair proposal, but we think it is important to explain them in detail. Fortunately, we are not alone. Following the EU’s landmark maintenance rights guidelines, the US Federal Trade Commission announced its intention to more actively implement the maintenance laws that have been enacted.

Inevitably, there will continue to be strong industry lobby groups pushing them to be downplayed against the wishes of consumers, so the more people who have the opportunity to discuss them, the better. Did we consider everything in the process of exploring this topic? Please let us know in the comments.